This is the third pieces about my 9+ years as a Governor and Lead Governor at my local NHS Trust. Part 1 describes what NHS governors do; part 2 shows how this has evolved and contributed to Berkshire Healthcare Foundation Trust (BHFT). This last part will include observations about how effective the governance process is. I intended to use the sub-heading “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly” but, arguably, that over-dramatizes the situation.

Contents Plus

- 1 Fun! Being a governor should be fun!

- 2 Due Diligence, Management, Staff, and Recruitment to the Board

- 3 Staff are our greatest asset

- 4 There’s quality and there’s Quality. And there’s the CQC

- 5 Who? Who should be an NHS Trust Public Governor?

- 6 Governor Elections: A Farce?

- 7 Public Engagement is part of the Governance Model

- 8 The role of Lead Governor

- 9 Governors in the NHS – Does it Work?

Fun! Being a governor should be fun!

If you don’t have fun, why do it? I spent more than twenty years of my life working for a company with a philosophy based on the ‘3 Joys’. If I could expect Joy from my job, I could very reasonably expect fun from voluntary activity such as being a governor in the NHS.

Joy comes from positive engagement, shared with colleagues. Can you imagine ‘Joy’ or ‘Fun’ in a Microsoft Teams meeting?

Governor engagement is not magic, but it does need some effort. Already Governors have a common interest in the Trust. Put them together in a room and they will interact.

Engagement with the Trust requires more than sharing publicly available documents. A few words with staff and managers over a sandwich after a meeting raises awareness. Meeting staff in a work context, but also socially builds relationships and deepens connections. There are many events put on by an NHS Trust for staff – briefings, training, workshops, award ceremonies, inspections, parties. All of these can accommodate a few governors without adding to the cost.

Covid restrictions limited social interaction. New ways of working save costs for staff who are time limited by removing the need to travel from meeting to meeting. Some governors felt this to be beneficial for them too, but I could see significant damage to the effectiveness of the Governor Team.

Due Diligence, Management, Staff, and Recruitment to the Board

Due diligence is about checks to avoid future trouble.

In its widest sense management should exercise due diligence in the NHS to make sure staff are carrying out their roles with consideration for patients and colleagues.

But how is due diligence exercised when it comes to appointments, particularly for senior management? I hope that Non-Executive Directors keep a watchful eye on the process because this is not something governors are party. One of our NEDs recruitment campaigns had HR experience as part of the job specification. The NHS Management Merry-go-Round could be a cause for concern: poor performers can promote themselves by moving from Trust to Trust.

Governors are involved in the recruitment of Non-executive directors. A governor has very little influence over an NHS Trust but, on the face of it the Appointments and Remuneration committee made up of governors plus the Trust Chair is an exception to this rule.

BHFT, like most Trusts, uses an agency to build up a list of candidates. The fees – from £15000 to perhaps double that – cover long-listing candidates, creating a short list in consultation with committee members, interviewing the shortlisted candidates, and checking references, and attending a number of meetings with the committee, as well as attending stakeholder events and being present for candidate interviews by the committee. Some agencies ‘groom’ candidates with training and placements so they have a list of potential non-execs ready and waiting, other agencies carry out searches based on the job requirements.

Checking the CVs of a long list of 20 or so candidates can be onerous, but it is important to have a personal view on the relative viability of the candidates. When a seemingly strong candidate is not recommended for the shortlist it is necessary to find out why; likewise those on the list that seem weak need an explanation. The agency representative can always justify their recommendations, but often these are made using incomplete information and assumptions. Influencing a shortlist is something governors can and should do. You may find resistance (“we don’t want too many on the shortlist, it will increase the costs / effort”), but everyone understands this is not the final judgement so those with opposing views will likely concede.

In my work role I was accustomed to scrutinising CVs:- the key is to focus on factors that are important to the role, but also to consider the documents’ overall credibility. In this case, for example, seniority in a large organisation and probity are key factors amongst others. Someone operating at board level in a company usually leaves footprints on the internet.

We had a candidate who wrote a letter emphasising his caring nature and how this drove him to work for a non-profit organisation. The implication was that he had sacrificed a career and personal gain for the well-being of others. I reviewed the annual reports of his company – his name was indeed present in the report, so was the word ‘profit’ – mentioned 15 times. His salary was 100s of thousands of pounds and he participated in a profit-share bonus. For me this was a red-line, a dishonest application.

When I explained my concerns to my colleagues on the committee, it became apparent that we governors were all stooges for the Chair. He had already decided this was his favourite candidate and refused to consider this new information. The other governors would not contradict him and the candidate was selected for the position, but not unanimously.

On another occasion the Chairman did not form part of the committee as we were recruiting his replacement. He had encouraged two Non-Executives on our Board to put themselves forward as candidates.

I applied the same scrutiny to the NED’s CVs as I did to the others. One of them I found had been a director of a number of companies that had gone bankrupt. There was legal action pending against some of his former colleagues. This put a big question mark against his candidacy for me. As far as I was aware there had been no problems in his behaviour as a Non-Executive, but I am sure this issue had not been explored by the recommending agency or the A&R committee when he was first recruited.

Without the Chair present we governors could make our own decision and fortunately there was a good outside candidate which we and other stakeholder could support.

As a committee member it is easy to abdicate responsibility, especially when confronted with so-called experts and very senior management. While governors may not be able to test a candidate’s technical ability, probing for honesty and openness can be executed by anyone with a bit of tenacity.

Understandably a Chair will want to recruit someone he can work with. They will avoid appointing a candidate who may challenge their authority, irrespective of what governors think. If the committee can’t agree with the Chair, they will most likely restart the recruitment process.

Some believe that widening the scrutiny of candidates can improve the quality of decision making. For me, stakeholder involvement is a matter of transparency and not for improving decision making. In my experience feedback from stakeholder groups rarely influence the committee members who spend much more time with more information on assessment of candidates.

Staff are our greatest asset

This is true in most businesses, but especially so in the NHS. At the Board, at Governors’ Council we should love the staff and really look after their well-being.

We want staff to be happy, to enjoy their work. To look after their ‘customers’ – for clinical staff, their patients, for administrative staff, their colleagues. At the beginning of this piece I indicated that governors should feel ‘joy’ in their role, ‘joy’ is what we should wish for staff!

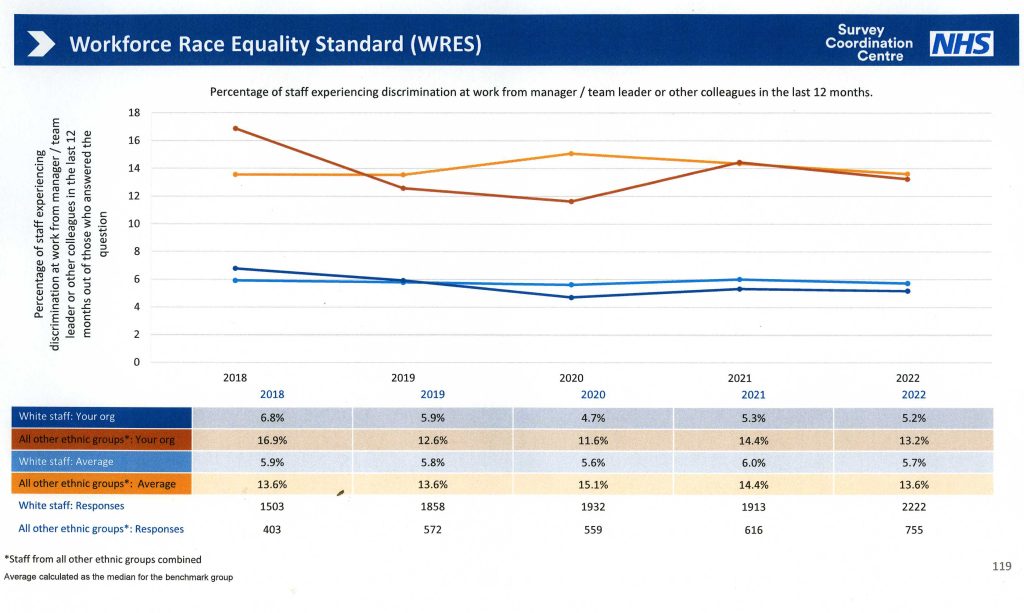

The staff survey is crucial for understanding the general picture. This requires governors’ attention! I was happy that participation at BHFT and many of the key measures showed an improvement year by year. It remains disappointing (also shocking because this is not new information!) that black and minority ethnic staff record a much lower level of satisfaction in their roles.

In a large organisation there will always be rogues. When I joined the Trust there was a clinician who had been fired. Over a number of years he had exhausted every avenue of appeal. His ‘last stand’ to create trouble for BHFT was as a governor. He nominating himself as Lead Governor, and his removal became the main focus for the Governors Council in my first year.

I visited a service where the manager had been in post since its inception, for more than 10 years. There were signs of dysfunction. I waited outside in the cold for 15 minutes with a man delivering lunches. No-one answered the bell and we only gained entry when someone left the building. The visitor log was full of strange scribble and comments. Rooms had been reorganised to accommodate one patient who was particularly anxious, and the normal entrance was blocked.

A few months later the CQC visited and the service went on special measures. Two contract managers implemented best practice processes with a renewed focus on patients. On my next visit it was unrecognisable.

It is hard to imagine how bullying can take place in a professional caring environment in the NHS. Maybe what is bullying to a fresh pair of eyes, is just a way of exercising control for a jaded and tired staff member. Visible bruises, however, verbal jokes at patients expense, treating basic rights as privileges which can be withdrawn abitrarily (for example the use of a phone), and withholding help are all real signs of everyday bullying of patients.

Moving staff around an organisation is one way of flushing out the rogues and abating complacency which is also an issues in parts of the NHS.

<Gagging Orders> Before I became Lead Governor I questioned the executive about staff who had been fired. I was particularly interested in those dismissed with a ‘gagging order’ which seemed not uncommon in the NHS. A gagging order is designed to stop the ex-staff member talking about the circumstances around their employment and/or dismissal. It is often the sign of a whistle-blower and arguably not a rogue! The situation was never made quite clear to me, and raising the matter seemed to embarrass my governor colleagues.

When I became Lead Governor a union representative asks me to be available to talk to an ex-employee. This person had been fired and had spent several years campaigning against the Trust. There were newspaper articles about her protests outside parliament. Although I agreed to talk to her she never go in touch.

In 2016 the NHS asked Trusts to appoint a “Freedom to Speak Up Guardian” as a channel for whistle-blowers. Statistics are collected and reported centrally about the use of the channel. This provides another route for staff members to relate their concerns (pre-existing possibilities included line-manager, union representative, staff governor, human resources).

Individual staff matters is not something governors should get involved in, but the general situation of course is a great concern. With the current shortage of personnel in the NHS, safe staffing features high on the Risk Register for most Trusts.

There’s quality and there’s Quality. And there’s the CQC

As a new governor I was invited to an introductory meeting with the Chair of BHFT. He suggested that I might eventually be chairman of the Governors Quality Committee. I had recently retired from a job with what felt like a lifelong focus on Quality so I demurred. Little did I know about the understanding or rather, lack of understanding, of quality in the NHS.

<The Care Quality Commission > I imagined the CQC (Care Quality Commission) would define Quality for the NHS. I found that the CQC was focussed on safe, effective, caring, responsive and well-led services. In other words this was ‘quality’ and not ‘Quality’. The CQC assesses organisations based on these 5 qualities or characteristics.

Does the CQC represent super-expertise in healthcare? I don’t think so. Many of the staff are on the same employment merry-go-round as the NHS. Inspections involve small teams and, inevitably there is a sampling approach. They talk to staff and management, and sometimes other stakeholders which may include governors, join some regular meetings, and look at records.

CQC inspections cause anxiety and wise management devote time and resources to training staff about the process and aims prior to the visit (which is usually pre-announced).

The inspection results in ratings for each service inspected and for the overall Trust. When a service is marked down as ‘requires improvement’ it almost certainly does, and resources will be allocated to this task ready for a revisit which takes place some months later. On the other hand a rating of ‘Outstanding’ provides a great boost to morale for staff and management and patients too! I imagine such a rating will also be a positive influence in bids for extra funding.

Remarkably services can move from ‘requiring improvement’ to ‘outstanding’ quite quickly. The reverse is true, too! A Trust marked as ‘well-led’ and ‘outstanding’ will likely have areas of desperately poor practice too.

<Quality Management> I was please when I was invited to the Trust’s Clinical Quality Conference. I attended this annual event 2 or 3 times in my early years as governor. I saw it as an opportunity to meet some of our innovators. Trust staff gave presentations about how they were improving their services and an outside speaker described healthcare best practice in the NHS and elsewhere.

A pin-board in the lobby outlined several different improvement initiatives. There was descriptive commentary, but explicit targets were completely absent. No performance measures probably means that problem analysis is superficial. Schedules and milestones, also absent, are key components of project management. I was so shocked that I grabbed the external speaker and asked him what he thought – he shrugged and seemed unsurprised. The Chairman who was present listened to my observation, but did not want to discuss this.

Most services in the NHS have limited resources and a rigorous approach to designing and re-designing clinical care processes and pathways is necessary to optimise these. It is unreasonable however to expect clinicians to take a project approach and work with processes (rather than people) without proper training. Much time and effort will be wasted.

A few years later governors heard that the Trust was investing in Quality Improvement training! This was a multi-year, whole organisation programme with the aim of embedding not only new skills, but a new culture where all could take responsibility for improving their work. Following pilot activity, the rollout and delivery and training is now managed mostly be internal staff. An organisation the size of BHFT has the scale to support a Project/ Programme Management Office that can train staff and provide quality assurance of project initiatives.

It is disappointing but not surprising that benefits are not quantified in a uniform way. It is impossible to say ‘the cost of the rollout over 2 years was X’ and the ‘ benefits and savings generated in this period was Y’. This is typical, not just in the NHS. Benefits Realization like Quality Improvement is a discipline which requires some skill and training to get results. Measures are rarely recorded or reported in the NHS unless they are mandated by Central Control (ie NHS-England).

<Service visits & Quality> Spending 2 hours on a Service Visit gives time to listen to staff and see the environment, and maybe therapy in action. It is also possible to see and talk to patients or carers. A governor can tune his / her antenna over a number of visits so it is sometimes possible to detect if things “aren’t quite right”.

I coined the phrase ‘looking at Quality with non-professional eyes’ when I was Chair of the Governors QA Group.

Sometimes governors were encouraged by the Director of Nursing to look at a service where there had been some difficulties or concerns. It is a challenge for senior management to visit such a widespread organisation often enough.

Students can be a good source of information. They are almost invisible to staff whereas senior managers and governors have quite a high profile. It was through intelligence from students that I learned about bullying of patients in a dementia ward, and some safety issues for staff in other wards.

On one occasion two governors visited a service and wrote a very favourable review. Shortly after I learned from a student that, for the very ill young people in this service, nursing care was quite dysfunctional. Patients were bullied, records were falsified, and care was mostly left to ‘care assistants’ who had never seen the patients’ care plans. Days later patients called the police to complain about staff and then left the facility which was supposed to be secure.

This is a Trust with a CQC assessment of ‘Outstanding’. It is always important to be vigilant in the professional care of people; unfortunately assuring quality of care across a large organisation is a ‘whack-a-mole’ exercise.

<Complaints and Compliments> When I joined the Trust the regular Patients Experience Report compared number of complaints against the number of compliments as if they offset each other.

Hold on a minute! What does a compliment mean? In most cases it means the staff member did their job! In some cases it may mean that extra time was spent on the grateful patient – at the expense of other patients. What can we learn from a compliment? Probably nothing. Is it a good thing? Yes it is good for staff motivation!

What is a complaint? It is a sign that the service is not working as expected. What can we learn from a complaint? Sometimes lots. At least we get the message that we should communicate better. Often we learn that the process need improving. A complaint can be the start of Service Quality Improvement.

Complaints and compliments are not equivalent. It is complaints that merit management attention. Compliments are for the staff!

Who? Who should be an NHS Trust Public Governor?

The purpose of the Council of Governors is to give citizens an opportunity to scrutinize their local NHS Trust and its services. Anyone living in the area could be a governor.

Publicly elected governors are always in a majority in the Governor’s Council. This shows the importance of independent members of the community exercising their rights and duties in the governance of the NHS. Alongside the Public Governors Trusts also have special interest groups – staff, politicians from local authorities, nominees from local charities, and sometimes patients’ representative.

Retired members of the NHS do notbelong. BHFT has 4 staff governors, and I have enjoyed working with them, but there is already enough NHS staff representation in a Trust that employs almost 5000 people. There’s a myriad of staff groups to solicit views and influence the Trust.

Retired NHS staff and managers who stand as public governors are blocking positions for other community members and are surplus to requirements. In my experience ex-employees of the NHS who become governors or Lead Governors pursue their own agendas and often do not fully grasp the governor role.

IN BHFT there are 6 Governors nominated by the 6 local authorities in our area. These are councillors, usually from the Labour or Conservative Party; sometimes they are good contributors to our Council. Councillors and ex-councillors who nominate themselves as public governors in addition to these 6 would do better to let other community members take these places.

Subject to these exceptions, anyone who is prepared to engage with the Trust and fellow governors, and give time to learn about the role and the operation of the Trust is a perfect candidate. The collegiate nature of governors’ work means that those who are angry about the NHS and the management of healthcare will likely be disruptive and unpopular unless they can put this to one side.

During my time there has continuously been governors who are also patients or ex-patients, and carers. There is no need to allocated specific places for this representation. Trusts however have an important duty to engage with patients and carers. There are many opportunities to do this and this is something that governors will want to see happening.

Some argue that is would be good to have young governors at the Council table. There is nothing wrong with this provided they can commit time and effort to the cause.

Governor Elections: A Farce?

As elections go, Governors Elections at NHS Foundation Trusts are a well-organised farce.

When I first became a Governor I was elected unopposed. Entry for nominations closed only days after the announcement reached members’ letter boxes. I was re-elected twice. On both occasions I beat several opposing candidates with a total of only 60 or 70 votes! In recent years the management of elections has been passed to the Electoral Reform Society, and the process runs smoothly, but the number of votes remains very low.

Trust members elect governors. BHFT has a catchment of almost 1 million potential patients. All are potential members, but there are only 7000. 175000 people live in the local authority area of Reading where there are 2000 members.

With these numbers – membership is not representative of the community served by the Trust; and governors most certainly are not representative of the membership in their area.

Who will be arriving after a new set of elections? I can imagine Trust Management waiting with baited breath. While the Governors Council controls and manages nothing, a dis-functional Council is disruptive. The Chairs of some trusts have resolved to reduce the number of public governors as a remedy – but of course this will not help.

Does it matter that public governors are not representative of their constituencies? Probably not. Wherever they come from, some governors will be effective and do the job as best they can, and others will not be great contributors. And disruptive elements can rise up from anywhere.

Public Engagement is part of the Governance Model

The Foundation Trust Governance Model is designed to include assessment by the local community. How can this operate if the local community don’t know what the Trust is?

In our area people can identify the local acute hospital and their GP, but other parts of the NHS have no recognition. Few know what BHFT is; even among the membership. This situation will never change without public engagement by the Trust.

Nearly all NHS Trusts fail in this area. Why? Because they are not assessed for public engagement. If there is no target, then there is no measurement and no management focus.

Some suggest that public engagement is the job of governors; this is the line taken by the employers’ organisation NHS Providers. But this is nonsense. Without public engagement by the Trust a large part of the governor’s job is undermined. The governors are volunteers and cannot compensate for this.

The role of Lead Governor

It is a requirement for governors to elect a Lead Governor – the purpose is to define a conduit for the NHS Centre to communicate with Governors. This is only used in extremis, possibly for failing trusts, and in my 5 or 6 years as LG I never received any Official communication.

I was advised by my new Chair that in his previous Trust the Lead Governor did nothing: – it was not a requirement for me to do anything!

I have described my contributions as governor and lead governor elsewhere, and I believe each person in the role can make it his own with there being almost no statutory responsibilities.

The position of Lead Governor for many is a focal point for communication within a Trust and this recognition is a good starting point. I valued my monthly meeting with the Chair and the informal contact with governors before and after committee meetings and council.

As Lead Governor it is possible to get the feeling and /or the recognition that you represent the Governors Council as a whole, but this is never the case. A more reasonable image is Lead Governor as servant and tool of the Governor’s Council.

Governors in the NHS – Does it Work?

Do governors play a significant part in the governance of their Trust?

The short answer is ‘no’. The Governor Council does not embody wide-ranging public scrutiny by the local community. The Council is not representative of the local community, and without public engagement, public scrutiny has no meaning. Secondly the Council does not have access to all areas, so members only have a limited view of the Trust’s operation.

We are all familiar ‘NHS Scandals’ – the irregular uncovering of poor performance in NHS Trusts. It is hard to believe that better Governors could have prevented these or alerted the public earlier.

Any sort of scrutiny, however, is beneficial to an organisation. It can encourage openness and honesty. A forum where an outsider can ask any question of senior management is likely to motivate them to keep their house in order.

There is no guarantee that an organisation will freely provide of information about its operation. In my case BHFT does provide support to governors and, on several occasions, when I had concerns about a service I was provided with information by senior management. This is not true of all Trusts.

How would a Trust’s performance be affected if the Governors’ Council did not exist? It is hard to imagine it being different. Press and Politicians have much more influence on the NHS.

The biggest beneficiaries of the system are the Governors themselves. Many are retired and they gain a new lease of life and stimulation through diligent application to the Governor role!